Truth Be Told (Part Two)

The People of Journalism

The News

Have you seen the news today?

That question usually means something has happened in the world that’s worthy of stopping what you’re doing and turning on the news or checking your news app. I’m one of those people. I love to know what’s happening in my community, my country, and around the world.

So, who determines what’s news? People do. They are known professionally as journalists. Some journalists are reporters, some are anchors, some are producers, editors, and managers. Each of those journalists plays an important role in deciding what the public reads, hears, and sees every day. Who are those people and why do they get to decide what’s news?

I mention this especially if you are a news consumer. It’s important to know who decides what’s news, and how and why they make their decisions. It’s obvious from watching newscasts, listening to news on the radio, and reading newspapers and online news, that the people behind the news have different perspectives about what’s news on any given day. If journalists do happen to cover some of the same stories, they often present conflicting information. Why is that?

The Blame Game

As I mentioned in recent newsletters, trust in the news media has fallen to new lows. How did that happen? Did modern news consumers become a tougher audience? Possibly, but I believe the news media needs to accept some of the blame.

Journalism is not a new or even recent communication tool. The Romans produced a daily journalistic publication during the 1st century BC called the Acta Diurna (Daily Events). It contained news of interest to people in Rome and was available throughout the city for people to read. Many other countries have published daily or weekly news reports through the centuries in a variety of languages. European countries had printed news publications as early as the 17th century. The first known publications in the English language were the Weekly Newes (1622), Berrow's Worcester Journal (1690), The Daily Courant (1702), and The Tatler (1709).

The first American colonial publication was called Boston’s Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick (1690). The first edition of the paper contained a story that was negative of the British government, so the government shut down the paper four days after it started. It would be 14 years before another newspaper was published in the colonies (The Boston News-Letter, 1704). That, and other experiences with government suppression of the press in colonial times, eventually led to including protection for “freedom of the press” in the First Amendment to the Constitution.

Journalism in the United States has a long history, which means journalists have had a lot of time to learn how to build and keep trust with the public. That’s why I believe the modern news media is at least partially to blame for trust issues with news consumers.

What Makes A Trusted Journalist?

That leads us to this question - what makes a trusted journalist?

I believe the best journalists have four things going for them.

They are —

Curious

Skeptical

Objective

Accurate

Let’s begin with curiosity.

curiosity - a strong desire to know or learn something — Oxford Languages

The desire to learn begins early in life. We start asking questions as young children.

“What’s that?” “Who are you?” “Where’s my mommy?” “How do you make that?”

Then there are the inevitable “why” questions. Everyone who has been around young children knows what I’m talking about. “Why?” “Why?” “Why?”

All of that is part of the human desire to know or learn something. Young children are curious about their world. How do they learn about the world? They ask questions — lots of them. The best journalists do the same thing.

Journalists wake up each day like other people. The difference is in what they do after they’re awake. The job of a journalist is to cover and report news of interest to the public “fairly and factually.” They should wake up with a strong desire to learn something that day — to be curious. A journalist’s curiosity will drive them to find out what happened in the world while they slept and how they can serve the public in following up on important stories and finding new ones.

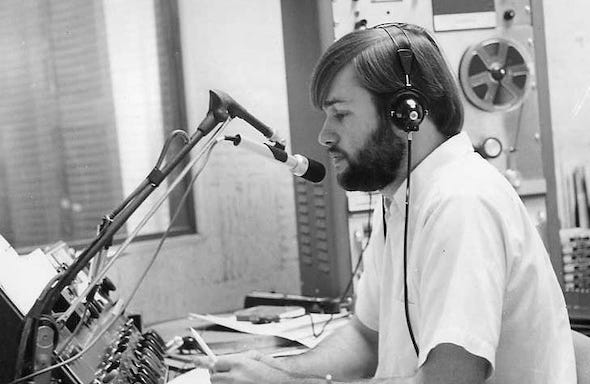

I used to have a rule as a news manager that every member of the news team come to work with at least three story ideas they could cover that day. I held myself to the same rule. We held two “story meetings” each day. The first was at 9am for dayside journalists and the second was at 2pm for nightside journalists. Each journalist shared their three ideas and we talked about how best to cover them.

The reason for the requirement was three-fold:

Come up with stories that would serve the public interest

Encourage journalists to be curious

Develop an environment of “original reporting”

Ask Questions — Get Answers

Journalists ask questions for a living. If they don’t ask questions, they can’t get answers. If they don’t have answers, they don’t have a news story to report. If they don’t have a news story to report, they won’t have a job for long.

So, what questions should a journalist ask? You might start by asking questions your audience would ask. How do you do that? Get to know your audience. Find out what they care about — what they want to know.

I sometimes wonder whether journalists have met their audience. Their reporting often appears to be aimed at themselves or people who are like them. Journalists spend a lot of time talking with other journalists in the newsroom, at news events, and after work. Some of my best friends in the world are fellow journalists, so I understand the desire to spend time with them. However, if you want to know your audience and be able to cover stories of interest to them, you need to spend time with them as well.

People love to talk about themselves, so ask people in your neighborhood and community questions about their life, family, job, and interests. Listen to their answers and show them you care about them. As you are curious about people and what they think, you will begin to understand your audience better. You will also come up with some great story ideas to take with you to the next story meeting at work.

You will also receive one of the greatest gifts that a news consumer can give you — feedback. My family remembers what it was like to go to the store or mall with me when I was a television reporter. People stopped us every few steps to talk with me about a story I had done. They were giving me their “feedback” as news viewers. My family would sometimes continue shopping while I talked with viewers and I’d catch up with them later. Those times of receiving viewer feedback helped me tremendously as a journalist. Listening to your audience and getting to know them is one very important way of building trust with them.

Original Reporting

I find that “original reporting” is often missing in today’s journalism. By that I mean reporting that originates with the journalist rather than with a news manager. A producer or editor may send a reporter out to cover a story (e.g. crime scene, building fire, school board meeting, public protest), but it’s up to the reporter to be curious and find something original to report about the story. How do they do that? By being curious and asking questions.

I had the public safety and courts beat for years, which meant I spent a lot of time at crime scenes, fires, police stations, fire stations, courtrooms, jails and prisons. The kinds of stories I came up with while covering my beat often depended to a large extent on my curiosity.

One of the first stories I covered as a television reporter decades ago was the brutal murder of a pregnant woman. It was a huge story that shocked the community. I was also a state correspondent for the Atlanta Journal and Constitution, and so I was calling stories into their editors each day in addition to my coverage for television newscasts and wire service reports. The police investigation eventually led to the arrest of two men who claimed the woman’s husband had paid them to kill her. That elevated the public’s shock level even more.

All of the reporters who covered the story followed the investigation and arrests. However, I thought something was missing from the story. I was curious about the toll this had taken on the murdered woman’s family. I was a husband and father and could only imagine how this horrible situation was affecting them.

I wondered if they would like to tell their side of the story, and so I contacted the parents of the murdered woman and asked them for an interview. They said they had watched my coverage on television and appreciated that I had been factual and fair in the coverage and had not tried to sensationalize the murder of their daughter and unborn grandchild.

The parents granted me an exclusive and in-depth interview that lasted almost two hours. We ended up doing a series of reports from the interview that gave the story more context. Many viewers thanked our station for broadcasting the series and giving the parents the opportunity to express their grief and anger.

That’s just one example of how curiosity can lead to original reporting. Every journalist can and should be doing original reporting — every day. It’s one of the things news consumers want from the news media.

Completing the Story

Many of today’s stories seem incomplete. When I watch a news conference, for example, hear a reporter’s questions, and later see or read that journalist’s report, it often lacks a sense of curiosity on their part. It’s painfully obvious that they could have asked a wider variety of questions and done more research into the answers they received that would have helped them fill out the story. Readers, listeners, and viewers are often left with many unanswered questions. Why? I think that it’s often because journalists aren’t curious enough to look deeper into the story.

That is disturbing to me on so many levels. We are living in one of the most complex and divisive periods in modern history. The public needs good answers to so many questions, but many of those questions are never asked by journalists. So many stories today are partial in information, scope, and perspective. Why?

There could be many reasons. It may be that journalists aren’t curious. It could be that they don’t know what questions to ask or how to ask them. It could also be that they have a personal or corporate agenda to fulfill. An editor or manager may be expecting a certain take on a story and the reporter knows they have to deliver that particular perspective to keep their job or earn a promotion. Whatever the reason, it’s not good for journalism or for the country.

Building The Future

So, how do we help this generation and the next generation of journalists develop the kind of curiosity that leads to original reporting? I believe it begins in colleges and universities where aspiring journalists begin to learn about real journalism and how to do it. I had the opportunity to speak to many journalism and communication classes as a news director years ago. It was always a pleasure to meet the students, share my passion for news, and answer their questions about working as a journalist. I later hired some of the students when they graduated. They applied for job openings and I hired them based on their curiosity and passion for news.

Building the future continues with news managers who hire journalists who are curious and interested in knowing the needs and interests of their audience. Managers need to hold their journalists to high ethical standards and require them to do original reporting — which comes from being curious and knowing the interests of news consumers. All of that can improve the public’s trust in the news media over time.

Journalists should be filled with wonder about the world and every story they cover. They should also appreciate the great responsibility they have constitutionally. The First Amendment to the Constitution protects the rights of journalists to do their jobs freely and without interference from powerful people who have biased agendas.

I often say that the most important story I’ve ever covered is the one I’m covering right now. Journalists should never rest on their laurels or awards. A news director told me when I was a young reporter that I was only as good as my last story. That thought drove me to find more and more stories through the years and for each one to be better than anything I had done before. I was curious then — and still am.

A Word to the Wise

Journalism belongs to you — the news consumer. So, a brief word to you about being curious.

Be a curious news consumer. Consume news from multiple sources that give you a broad view of local, national, and world news. Search for journalists who demonstrate curiosity in their stories. Listen to the questions they ask in news conferences and interviews. Are they asking the questions you would ask? Watch, listen or read how they report the news. Are they getting information from all sides of a story? Does their reporting seem complete? Also, look for journalists who do original reporting. That’s often a way to spot a curious journalist.

You have a lot of choices in news coverage these days, so use your choices wisely.

Next Newsletter

We’ll look at the importance of journalists being skeptical in our next newsletter.

Comments Welcome

I hope these thoughts are helpful to you as a journalist or news consumer. Please share your comments and I’ll respond as quickly as I can. If you like what we’re doing in this newsletter, please let your friends know about it so they can subscribe.

Newsletter Purpose

The purpose of this newsletter is to help journalists understand how to do real journalism and the public know how they can find news they can trust on a daily basis. It’s a simple purpose, but complicated to accomplish. We’ll do our best to make it as clear as we can in future newsletters.