What Is Journalism?

Look up “journalism” in an encyclopedia or dictionary and you find this:

the collection, preparation, and distribution of news and related commentary and feature materials through such print and electronic media as newspapers, magazines, books, blogs, webcasts, podcasts, social networking and social media sites, and e-mail as well as through radio, motion pictures, and television. Britannica.com

the collection and editing of news for presentation through the media … writing designed for publication in a newspaper or magazine — Merriam-Webster

Those are accurate definitions, but let’s see if we can boil it down to three words —

factual story telling

Story Telling

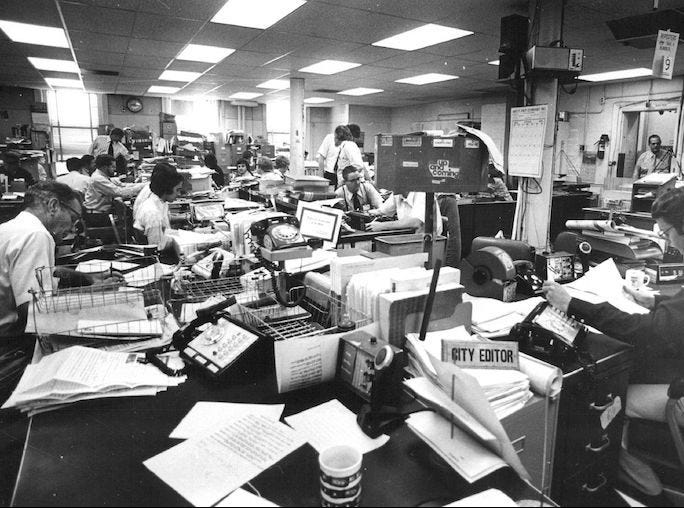

Courtesy: New Jersey Globe

For the sake of brevity, I’ll use broadcast terms in this newsletter. Print terms are a little different, but the basics of what happens in a newsroom are about the same. Print birthed broadcast in the early 20th century, so similarities should be expected.

Journalists hear the term “story” all day long in the newsroom. Reporters are assigned their “stories” to cover in a morning or afternoon meeting. Producers are assigned their “stories” for their newscasts and they develop a “story rundown” (also known as a “story lineup”) to show their executive producer (EP). Once the EP approves the story rundown, everyone in the newsroom understands what happens next. Reporters know how long their story will run in the newscast and where it will run. They’ll also know if any part of their story will be live in the studio or in the field (away from the station).

News anchors read story information that reporters write for them. The anchor “script” usually appears on a teleprompter so the anchor can continue looking into the camera. What the anchor reads before the reporter speaks is called the “intro.” What the anchor reads after the reporter speaks is called the “outro.” If the reporter is live in studio or in the field, the anchor may ask a question the reporter wrote for them or ask their own question.

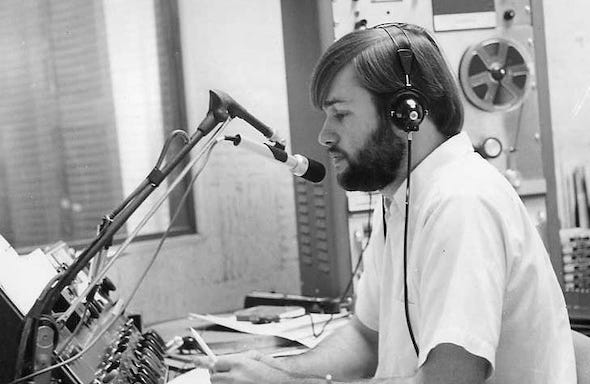

That’s the basic process of television news day after day, night after night. It’s been going on for decades and may continue for years to come. Though technology has changed a lot since my first on-air report in 1967, the idea of journalism being factual story telling is about the same.

Telling A Story

If journalism is “factual story telling,” then anyone can be a journalist. Right? Well, yes and no. Anyone can tell someone a story that’s factual. Anyone can “keep a journal” of events in their life and let other people read it. We might call that unpaid personal journalism. However, I think it’s good to understand that the heart of all journalism is telling factual stories.

What you do when you tell a story to a friend or family member is similar to what a paid professional journalist does (or should do) — tell stories factually. I use the adjective “factual” for an important reason. People often tell stories that are either not factual or are missing facts necessary to understand the truth of a story. We used to call that “telling a story,” meaning something about the story was not true (factual).

When I was a child, telling a story often led to bad consequences. We would first have to apologize for “telling a story” (lying). We might also get a spanking and be sent to our room to “think about what we had done.” That may sound harsh in today’s parenting standards, but it worked pretty well in my day. We learned that telling stories (lying) had unpleasant consequences.

Professional journalists can do the same thing. Instead of “factual story telling,” they can tell a story — meaning that something about the story is not factual. You’ve probably heard the term “fake news.” When someone says a journalist or journalism organization does “fake news,” they mean some of the reports are not true.

Journalism organizations (e.g. radio, television, newspaper, magazine, online) should have a system of checks and balances to catch errors (intended or unintended) before broadcast or publication. Managers have the responsibility of monitoring stories throughout the day to ensure they are factual. If they are good at their job, managers (e.g. news directors, editors, executive producers) will spot information in stories that don’t pass the “smell test” — something about the story doesn’t smell right. The manager tells the reporter (writer) about their concern. If they don’t like the response they get, the manager directs the reporter to do whatever is necessary to get the story right. At least that’s the way it’s supposed to work.

Can a story with false or misleading information get into a newscast or publication? Yes. What should managers do when they find out? Here’s an example from many years ago when TV stations had a small number of newscasts each day. Keep in mind this was before computers and the Internet.

I was a television assignment editor at the time. My job was to assign stories to reporters in the morning and work with them during the day to cover those stories. The reporters returned to the station and wrote and edited their stories for the evening newscast. The executive producer and show producer handled the details of story accuracy at that point. I turned my attention to the night news crew and what they would cover for the late newscast.

The news anchor came to me after the evening newscast and asked me about something in a reporter’s story they thought was wrong. I looked at the written script and it didn’t match what the anchor said he had read on the air. I called the reporter to my desk and asked him about the story script. He said the script was what he had written and that the anchor must have read it incorrectly. Something didn’t feel right, so I did a little investigating.

In the days before computers in newsrooms, reporters used special script paper that had five or six pages. Each page below the top page had carbon paper so whatever a reporter or producer typed would go through all the pages. The top page went to the teleprompter for the anchors to read. The other pages went to the anchors, reporter, producer and technical director. I gathered all of the script copies for the story in question and they all supported what the reporter had said. However, I still wasn’t convinced.

I got an idea and it solved the mystery. I looked through all the trash cans in the newsroom and other areas of the station and found one script crumpled at the bottom of one of the cans. I unfolded the paper and there was the original teleprompter script with the information the anchor said he had read on the air. What I found in the trash can did not match the teleprompter script the reporter said he wrote.

I took all of the scripts, including the one I had found in the trash can, to the news director. He talked with the anchor, the producer, then with the reporter. After seeing the evidence, the reporter admitted he realized his mistake after he heard the anchor read the script live on air. He was afraid the mistake would get him fired, so he quickly wrote a new script with the correct information and secretly exchanged all of the copies with the incorrect script after the newscast. He thought he had disposed of all of the incorrect copies in a way that no one would discover, but he forgot about the one he crumpled and threw into a trash can.

The news director fired the reporter on the spot. Why? Because he had made a mistake? No, because the reporter lied to cover up his mistake. The news director told me he would not have fired the reporter if he had been up front about the mistake instead of trying to cover it up.

My Mistake

Journalists are human and do make mistakes. Some may be small points where something could have been said more clearly. Some may be large points where what was said was not factual. Journalism has a way of dealing with mistakes of all sizes.

Journalists can do a variety of things when they get something wrong in a story. They can clarify, correct or retract. The goal is to be accurate and objective. Truth is the goal. If a journalist gets something wrong in a story, they should make it right.

Clarification — “the action of making a statement or situation less confused and more comprehensible” (Oxford Languages)

Correction — “a change that rectifies an error or inaccuracy” (Oxford Languages)

Retraction — “a withdrawal of a statement, accusation, or undertaking” (Oxford Languages)

“Corrections policies are an unequivocally good thing about journalism. Even as accusations of “fake news” dog the industry, its response should be to double down on this practice.” Poynter, 2019

Then there’s the important point about where in a newscast or publication a clarification, correction or retraction should appear. I had a rule as a news manager that clarifications, corrections or retractions of any story should appear at the same place in a newscast during the same time period. For example, if a journalist made a mistake in a story that ran as story #1 in the 6pm newscast, the clarification, correction or retraction should run as story #1 in the next newscast following the discovery of the error (e.g. 11pm) and the first 6pm newscast after the error was discovered (next day). The reason was to do everything possible to reach the same audience of people that saw the original story. They need to know about the mistake and get the right information.

Another rule was that the correction or retraction should air long enough for people to clearly understand the error and the attempt to make it right. A one-sentence correction does not make up for a two-minute original report on television. The clarification, correction or retraction should include enough information to add context and understanding to the reason behind the station, network, or publication’s update.

Many corrections to stories are buried at the end of television news blocks or somewhere deep inside the back pages of a newspaper or magazine. That’s not right. That’s not honest journalism. If a news organization makes a mistake, it should own up to it and give the correction the same prominence as the original story.

Unfortunately, in our 24/7 world of newscasts, publications and social media, clarifications, corrections and retractions don’t have the same impact on the public they had even 20 years ago. Once wrong information is reported and circulated, it’s almost impossible to reach the same people who heard or read the original news story.

Unfortunately, many people read only headlines to news stories. Some only see the headlines on social media rather than in the actual newscast or publication. They often don’t see that the original publication made a clarification, correction or retraction to a story. Once the headline information is out there, it is rarely changed or taken back. People believe what they remember reading and continue thinking something to be true even though it was discovered to contain incorrect information.

Even people who see a corrected or retracted story often continue to believe what was reported originally. That’s another reason for journalists to get their stories right the first time and not depend on clarifications, corrections or retractions.

The American Press Institute has some helpful suggestions for journalists about writing corrections to stories.

Surprised?

You may be surprised by what I just shared because so few journalists and news organizations make any attempt at correcting factual errors in their stories. Even though news organizations like Poynter and The American Press Institute recognize the importance of correcting stories, it’s rare to see news organizations do it today. Some have even been caught deleting wrong information in their online editions without mentioning that they had made an earlier mistake. That used to be grounds for dismissal years ago. Why not now?

Grumpy?

No, I am not the grumpy old man. I'm not upset with today’s journalism because it’s not the way I used to do it years ago (“in my day” — SNL skit). What upsets me is that somehow journalism changed without having a good reason for changing. The rules and standards that guided journalists for decades have been cast aside by many for some reason. Knowing that reason will help us understand what has happened to journalism and why. That’s the purpose of this series of newsletters.

Grumpy? No. Deeply concerned? Very and here’s why.

Axios reported a year ago that trust in the media hit a new low.

56% of Americans agree with the statement that "Journalists and reporters are purposely trying to mislead people by saying things they know are false or gross exaggerations."

58% think that "most news organizations are more concerned with supporting an ideology or political position than with informing the public."

Last summer, Poynter quoted a report that the United States ranks last in media trust at just 29%. That’s worse than Brazil, Canada, Poland, the Philippines and Peru!

Gallup reported last October that Americans' Trust in Media Dips to Second Lowest on Record.

Americans' trust in the media to report the news fully, accurately and fairly has edged down four percentage points since last year to 36%, making this year's reading the second lowest in Gallup's trend.

Gallup started tracking the public’s confidence in the media and other key U.S. institutions in 1972 — almost five years after I became a journalist. I’ve watched the Gallup polls through the years, and the growing distrust of the public in journalism and the three branches of government causes me great concern. The trend continues in the wrong direction, and that does not bode well for the future of our country.

Comments Welcome

I hope these thoughts are helpful to you as a journalist or news consumer. Please share your comments and I’ll respond as quickly as I can. If you like what we’re doing in this newsletter, please let your friends know about it so they can subscribe.

Newsletter Purpose

The purpose of this newsletter is to help journalists understand how to do real journalism and the public know how they can find news they can trust on a daily basis. It’s a simple purpose, but complicated to accomplish. We’ll do our best to make it as clear as we can in future newsletters.

"Last summer, Poynter quoted a report that the United States ranks last in media trust at just 29%. That’s worse than Brazil, Canada, Poland, the Philippines and Peru!"

This paragraph is so loaded. Except for the grace of God, civilisation as we once knew it has crumbled, THE EMPIRE HAS FALLEN.

Thank you Mark. I was particularly interested in subscribing to your newsletter because I have been a passionate consumer of news media since a young girl growing up in the UK. My ambition since a child was to be a journalist at the BBC so I studied Media Studies, Politics and English to pave my path in that direction. However as I often like to say, 'God had other plans'! I ended up pursuing a technology career BUT (God does have a sense of humour) ended working for the BBC for 14 years, followed by the Murdoch Group of papers (where I currently work). I therefore speak as an insider, and I too have noticed the decline from within. But I tell you what: my eyes were already open, because since my secondary (High School) school age, I have been obsessed with the subject of media corruption. It was sparked by Princess Diana's death which was the first time I encountered the term 'papparazzi' and I was intrigued by their practices . Around that time I really began to see a bigger picture of the media along with its tendency to massage the truth in order to 'break' a story. Since then the media has increasingly positioned itself as the gateways to global information dissemination, and essentially the 'arbiters of truth', but as we know, with such great power comes great corruption.

Harking back to my student days, I made a name for myself as a great essayist, but its funny, I do not remember many of them....but one I DO remember vividly is that prescient piece I wrote about foreseeing a day when the media will be a god-like monolith on the universe, to the extent that governments and large corporations will flock to them to achieve their twisted ends but, alas, I did not want to live to see that day.