Counter Views About Ethical Standards

The View from a Younger Generation of Journalists

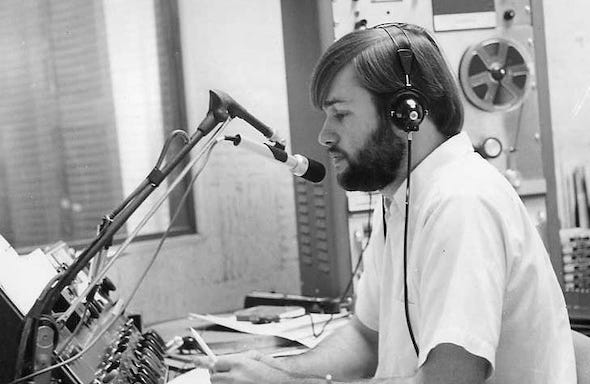

I am the product of my training under the mentorship of journalists who preceded me, plus decades of experience both as a reporter and as a news manager. The fact that I did my first live on-air news report in 1967 means that my bosses began their journalism careers during the 1940’s and 50’s.

I’ve worked in radio, television, newspapers, and online. I’ve also reported for wire services, radio and television networks, and written articles for magazines during a career that spans almost 60 years. That makes me an ‘old timer’ in the eyes of many of today’s young journalists.

However, being an older journalist doesn't mean I don’t understand the challenges of today’s news media. I do. However, what I don’t understand is why many young journalists want to ‘change’ the profession’s ethical standards to ‘something else.’ I continue to believe that accuracy and objectivity are hallmarks of doing ‘real journalism.’ There’s an historical reason for that —

Objectivity hasn’t always been a cornerstone of journalism. American publishers first turned to objectivity in the early twentieth century, in response to the freewheeling “yellow journalism” common at the time. Readers embraced it, grateful for a withdrawal from sensationalism and opinionated coverage.

American journalist Walter Lippmann, one of the early champions of objectivity, saw the dangers posed by propaganda masquerading as news and argued in 1920 that the “sensible procedure in matters affecting the liberty of opinion would be to ensure as impartial an investigation of the facts as is humanly possible.” Columbia Journalism Review

With the advent of schools of journalism in the early part of the 20th century (e.g. University of Missouri, Columbia Journalism School), graduates began entering the journalistic workforce. Their training, especially given the emphasis on professional ethics, made a difference for journalism in the years and decades that followed. The graduates helped change journalism from the freewheeling ‘yellow journalism’ into a profession that Americans eventually came to trust as credible and reliable.

Journalists’ formal training in gathering and confirming facts, developing trustworthy sources, and presenting their stories in a balanced way were a large reason for the change through the 20th century. Years of experience under the leadership of news managers committed to honest journalism brought the profession into a position appreciated by the American news consumer.

Another reason was the ‘separation of news from opinion.’ I remember well as a child in the 1950’s that local television stations had separate ‘commentary’ or ‘editorial’ sections that were identified as not presenting the views of station management or the news department. The person presenting the editorial was usually identified as the ‘editorial director’ or ‘spokesperson.' That was an important part of developing trust among the station’s audience. Journalists were not allowed to express personal opinions on air or in any other public venue. Doing that would often end with suspensions or firings. Personal opinions were just that — personal. They had no place in the profession of journalism.

Newspapers had similar policies in having separate news and editorial sections. Readers knew what they were getting, unlike many news stories today that mix news with opinion.

So, with that background I’d like to give younger journalists an opportunity to explain why they want to ‘change’ journalism’s professional standards. I will respond to their reasons and concerns in the next Real Journalism newsletter.

Why Change?

It is conventional wisdom among journalists that while the world around us changes, our ethics do not. Yet a fresh look at our standards and practices seems a worthwhile pursuit at this moment. Trust in the press has declined. Politicians lie to the media and to the public, and we have to decide how to cover those lies. Internally, journalists are debating the merits of objectivity in the approach to news, and how to best protect their sources. The rise of nonprofit newsrooms brings new questions about funding. And the rapid growth of AI presents new quandaries. Columbia Journalism Review (CJR)

Perhaps the most basic task of journalism is to distinguish truth from falsity. To identify the facts, and to present those facts to a readership eager for information. Journalists may once have believed that their responsibility stopped there—but in today’s media environment, it’s become clear that delivering facts to the public is not so straightforward. Distinguishing true from false, which often entails calling attention to false information, risks amplifying and even legitimizing that information. There is no better contemporary example of this problem than the media coverage of Donald Trump.

“Our norms and conventions of how we cover politics and politicians were not created for a president like Donald Trump,” Rod Hicks, director of ethics and diversity at the Society of Professional Journalists, says.

Hicks questions the utility of “both sides” journalist protocol in covering politicians who’ve taken cues from Trump on manipulating the press to their advantage. “Every side doesn’t deserve equal weight,” he said. “It’s actually misleading your audience if you give too much weight to something that evidence says is not valid. We think that we’re doing our jobs by following this both-sides rule, but we really aren’t.” CJR

… in recent years, as newsrooms have diversified beyond the white, Western, and male culture upon which it rests, this approach has been scrutinized. Should journalists reconsider the ethical merits of objectivity, and if so, how?

In his 2010 criticism of the view from nowhere, NYU journalism professor Jay Rosen wrote that this idea has “unearned authority in the American press. If in doing the serious work of journalism—digging, reporting, verification, mastering a beat—you develop a view, expressing that view does not diminish your authority. It may even add to it. The ‘view from nowhere’ doesn’t know from this. It also encourages journalists to develop bad habits. Like: criticism from both sides is a sign that you’re doing something right, when you could be doing everything wrong.”

The question of “whose social order you’re maintaining” hits especially hard for journalists from marginalized communities, many of whom question how objectivity may reinforce or neglect to correct racist, sexist, or transphobic ideologies. While journalists, including Rosen and Callison, had long been raising questions around journalistic objectivity, nothing served to decenter objectivity-as-central-tenet more than the 2020 death of George Floyd and the racial reckoning in the media industry that followed.

Former Washington Post reporter Wesley Lowery published an op-ed in the Times challenging the “gaze of white editors” and calling out the industry’s failure to recruit and retain journalists of color. To his point, a 2022 Pew survey of twelve thousand working journalists found that only 6 percent of journalists are Black, 8 percent are Hispanic, and 3 percent are Asian.

“Since American journalism’s pivot many decades ago from an openly partisan press to a model of professed objectivity, the mainstream has allowed what it considers objective truth to be decided almost exclusively by white reporters and their mostly white bosses,” he wrote. “And those selective truths have been calibrated to avoid offending the sensibilities of white readers. On opinion pages, the contours of acceptable public debate have largely been determined through the gaze of white editors.” (In May, CJR published an investigation in which several women alleged that Lowery sexually assaulted them.)

Lowery’s critique of objectivity gained support across the industry. A Nieman Lab survey of articles about objectivity from the Columbia Journalism Review, Nieman Journalism Lab, and Poynter written between 2020 and 2022 found that the vast majority took a “very negative” or “somewhat negative” view of the concept.

Stephen J.A. Ward, a lecturer in ethics at the University of British Columbia and the author of several books on media ethics, believes that digital media calls traditional ethics into question. He questions the value journalists place on telling both sides of a story.

“I mean, does anybody reporting on child abuse go and get the other side? No, there is no neutrality,” he said.

“The consensus among younger journalists is that we got it all wrong,” Emilio Garcia-Ruiz, editor in chief of the San Francisco Chronicle, told former Washington Post executive editor Leonard Downie Jr. They believe: “objectivity has got to go.”

“There is definitely a generational tension going on right now in newsrooms between traditional notions of things like objectivity and younger journalists who are more comfortable with advocacy than their older mentors and editors and news directors may be,” said Kathleen Culver, director of the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. CJR

You may also find these articles helpful in understanding why some younger journalists want to see change in journalism’s ethical standards —

Thirteen Journalists on How They Are Rethinking Ethics

Times Change, and So Can Ethics: Journalism needs new guidelines to face new challenges

It’s Time for a New Look at Journalism Ethics

Next Newsletter

I believe that younger journalists should be listened to carefully and responded to respectfully. I will share my thoughts about their concerns in the next Real Journalism newsletter.

Comments and Questions Welcome

I hope these thoughts are helpful to you. Please share your comments and questions and I will respond as quickly as I can. If you like what we’re doing in this newsletter, please let your friends know about it so they can subscribe.

Newsletter Purpose

The purpose of this newsletter is to help people who work in the fields of journalism, media, and communications find ways to do their jobs that are personally fulfilling and helpful to others. I also want to help news consumers know how to find news sources they can trust.

[The Real Journalism Newsletter is published every other Tuesday morning — unless there’s ‘breaking news!]